TVA's client Bill Dohr gave a $15 million promissory note to buy a real-estate development company from his partner and father-in-law, Bob Lintz. Given their close ongoing business and personal relationship - and because the California real estate market in the early 2000s was flowing with milk and honey - the parties were not terribly concerned with documenting the payments on the note. But after Lintz's health declined, his fourth ex-wife and then fifth wife (long story) usurped control of the trust, stole millions from Lintz, and sued Bill on the note, in a case styled Shapiro v. Dohr, et al. TVA's Tom Vogele and Tim Kowal went to trial prepared to show the note was paid.

We were shocked, however, to learn that the plaintiff didn't actually have the note! And further shocked - and dismayed - to learn the trial judge did not understand it was required. Few would suppose, after all, that someone would ever walk into a bank with a photocopy of a check, and expect to walk back out with cash. Yet the plaintiff and the trial court operated under that premise. The entire trial was a curiouser and curiouser experience.

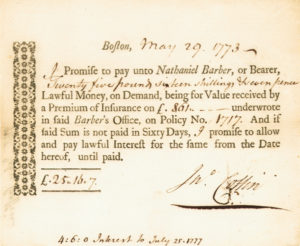

Outside of Wonderland, of course, promissory notes - and checks, in case you are getting any ideas - are governed by the Uniform Commercial Code (codified in the California Commercial Code), which requires the original before it may be honored. The sole exception to the rule that requires the plaintiff to bring the original, wet-signature note to trial is Commercial Code section 3309. Section 3309 requires plaintiff to prove:

The court heard all about the looting and usurpations from Lintz's estate, which had never been fully accounted for. The trial court even allowed that the fourth-ex-turned-fifth wife might have made off with the original note, too. This is probably why the plaintiff did not even attempt to prove any of the required elements under section 3309. Yet the Orange County Superior Court gave a judgment on it anyway.

No findings, and no evidence to make them. If we had ham, said Groucho Marx, we could have ham and eggs... if we had eggs.

We duly advised the Court of its omission, explained the Commercial Code to it, but the Court stood on its judgment. As Lewis Carroll's Red Queen said, "Sentence first! Verdict afterwards!"

The Court of Appeal reversed. The Court noted that, even where findings are missing, a reviewing court generally will infer the trial court intended to make the missing findings. But in this case, the Court of Appeal was forced to observe that TVA covered all its bases and preserved the issue to be duly reversed on appeal:

Dohr's primary contention is the findings in the court's statement of decision are insufficient to support the judgment in the Trust's favor, and because he brought that insufficiency to the court's attention prior to entry of judgment, we cannot infer those findings in support of the judgment. He is correct.

With these words, the $5.1 million judgment - worth over $6 million with interest by the time of the opinion - was vacated.

(Interestingly, however, the Court of Appeal perpetuated the incorrect doctrine on judicial admissions expressed in Barsegian v. Kessler & Kessler (2013) 215 Cal.App.4th 446, which we unfavorably reviewed in our April Newsletter.)

Justice - and sanity - were delayed, but not denied.

Tom and I thank our former professors at Chapman's Fowler School of Law, Celestine McConville, Lawrence Rosenthal, and Nancy Schultz, for furnishing an invaluable "murder board" to prepare for the oral argument before the Court of Appeal.

Timothy M. Kowal, Esq.

Shareholder, TVA